August 2025

Why was the "I" created?

A hard trick set by the brain

Shigeru Shiraishi

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@iÎ@Îj

There is the Japanese version. If you are interested in it, please check the following URL.

https://www.why-i-created-j.com

If you're using a smartphone, it would be easier to read if you choose the smartphone version.

Smartphone version@https://www.why-i-created-s.com

| 1@Outline and supplementary explanation of the paper "Where is the mind?" |

2@Main ThemeFWhy was the "the "I" created? | 3@Doenload PDF File |

4 OpinionsEComments> |

Table of contents

Foreward

Chapter 1 Outline and supplementary explanation of the paper "Where is the mind?"

(1-1)The apparent world

(1-2)Re-examination of "the existence of the eIf"

Additional explanation

Am I looking at something?

Am I thinking about something?

(1-3)The definition of the "I" inherent in the world of the mind

The thought of the gIh

Sorting out the words

Explanation by using figures

Summary of "Where is the mind?"

Chapter 2: Psychological Space

(2-1) Characteristics of psychological space

(1) The positions of the objects do not match

(2) Superimposition of characteristics

(2-2) Existence and Recognition

Chapter 3: Why was the "I" created?

(3-1) Two elements and two systems that make up the "I"

(1) Apparent body

(2) Apparent Mind

(3) Apparent Acts

(4) Systems of Superimposition and Synchronization

(3-2) The existence of the gIh in the world of the mind

(1) The "I" inherent in the world of one's own mind

(2) The meaning of being a copy of the external world

(3) Creation of the thought of the gIh from the apparent acts

(4) The Role of memory connecting two worlds

(5) Why was the gIh created?

Summaryof this paper

Addendum

Afterword

Self Itroduction

Address of Papers

Foreword

@You may be wondering from this title, gIs this a philosophical story? or about religion? or trying to talk about morality?h But it is not. I have already uploaded a paper on the Internet named "Where is the Mind?". This paper is a sequel to that paper, and it is an attempt to further delve into "the existence of the eIf" from the standpoint of science.

@For those who have already read the paper "Where is the Mind?", I think it is unnecessary, but I would like to first give an overview of the paper, and a supplementary explanation, and then get to the main topic of this paper. The URL of the papers "Where is the mind?", and that of "What am I?", and "What is ebeing visiblef?h which will be cited later, are shown in the "Address of Papers".

Definition of the words

@Before beginning, I would like to explain four things about the use of words. The first is why, as the title of the paper suggests, is it written as the "I" with a quotation mark? This point will be explained in detail later at section (1-3) gThe definition of the "I" inherent in the world of the mindh, so for the time being, you may continue reading with a general interpretation.

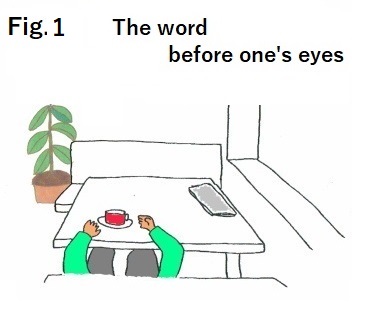

@The second is the meaning of the words, "before onefs eyes " such as "the world before our eyes " and "the world seen before our eyes", which will be used frequently from now on.

@Please look at Figure 1. At first glance, it is a picture with a strange composition, but it is the world that I or you see through my or your eyes. In other words, it is the world that we can see when we open our eyes, and we cannot see when we close our eyes. The world will be expressed as "the world before our eyes " or "the world seen before our eyes ". It will be explained later at section (1-P) hthe apparent worldh but what is indicated by these are not about the material world. I hope you will keep this in mind.

@Third is the word "apparent", which will be also used frequently. It is used in two ways. Namely, it will be used as "existence" or "act", but this will also be explained in detail later in section (1-3) gExplanation of wordsh. For the time being, please think of it means "something different from what is considered by common knowledge".

@Fourth is how to use glookh and gseeh. In Japanese, g©éh(miru) is used only as a transitive verb (vt.) and not as an intransitive verb (vi.). On the other hand, "©¦éh(mieru) is used only as an intransitive verb and not as a transitive verb.

@In translating this paper into English, glook ath is used as a transitive verb, and gseeh and gbe seenh are used as intransitive verb, in addition to them gbe visibleh is used as the same meaning of gbe seenh. I am wondering about if there is a difference from the original usage of English, but I hope you will keep in mind that they are going to be used as such meanings./p>

@For example, I will indicate as follows when we are turning our gaze to a coffee cup,

I look at a cup. (vt.), I am looking at a cup. (vt.),

and indicate the cup which appears in our field of vision because of gazing it as follows.

I see a cup. (vi.), A cup is seen. (vi.), A cup is visible.Chapter 1: Outline and supplementary explanation of the paper "Where is the mind?"

(1-1) The apparent world

@It all starts with the understanding of the fact that the world we see before our eyes is the " apparent material world" created by brain activity. This was the first point of discussion in the afore mentioned three papers. From this fact, we can derive the fact that our own body that we see before our eyes is also an "apparent body" created by brain activity. Furthermore, if we define the world created by brain activity as the world of the mind, then the world that we see before our eyes, including our own body, is the "world of the mind." Of course, this is under the premise that the material world and the physical body exist.

@It is relatively easy to understand that the world we see before our eyes is not the material world, but the apparent material world, and there are many people who claim to do so, even if they do not specialize in philosophy, psychology, or cognitive science. However, it seems that the number of people who claim that their body seen before their eyes is an apparent body created by brain activity is small. I understood relatively early that the world before my eyes is the apparent material world, but it was a mystery why the apparent material world created by brain activity exists outside of my own body. I had assumed that my body seen before my eyes is my physical body. The mystery was solved by a surprisingly simple reason.

@If the world we see before our eyes is the material world, there will be many contradictions. One of them is the "counterexample of color". Namely, color does not exist in the material world. Electromagnetic waves reflected at objects as substance form an image on the retina of the eyes, which are converted into electrical signals and reach the brain. Colors are created by brain activity, and they color the world before our eyes. Therefore, it leads to the conclusion that the world before our eyes is not the material world, but the apparent material world created by brain activity. If we extend this logic, we can see the skin color at our body before our eyes. Therefore, the body before our eyes is also an apparent body created by brain activity. However, I don't think that this explanation will convince you, but there is no doubt that the interpretation of our own body before our eyes is hindering our understanding of the world before our eyes.

@If we assume that the world before our eyes is the material world, various contradictions will arise, such as the "counterexample of color" that I have mentioned just now. In the same way, if we assume that the body before our eyes is the physical body, there also arise some contradictions. For more information, see Chapter 3, Section 4 of the afore mentioned papers "Where is the Mind?", or see Section 3-2 of "What am I?". It is explained in detail, so I would appreciate it if you could refer to it.

@This paper begins from the starting point that both the world and our body we see before our eyes are the gapparent material world" and the gapparent physical body" created by brain activity. You may think, "It is too stupid to keep up a contact with your story.", but I would appreciate it if you could stay with me for a while. I'm not going to talk about mere suggestions or guess. I will proceed with the story in a logical way.

(1-2) Re- examination of "the existence of the eIf"

@Another point in the afore mentioned three papers was that what we assume as "I" in daily life is an gexistence inherent in the world of our own mind" actually. In this paper, from the viewpoint that the mind is created by brain activity, and that the body and the mind are qualitatively different, but they are inseparable, the story starts by defining "I" as follows,

@gIh = my body + my mind @

@Common knowledge tells us that gmy bodyh is a physical body that exists in the material world, and that gmy mindh is an abstract being, as indicated by the words; intellect, emotion, and will. Of course, there is nothing wrong with defining the gIh in this way.

@From common knowledge,

gIh = my body + my mind (abstract existence as indicated by intellect, emotion, and will) A

@However, it is important to note that we are not talking about the material world, but about the "world we see before our eyes", that is, "the world of the mind created by brain activity". Therefore, "my body" is the one that we see before our eyes, and as I have just said, it is the "apparent body" created by brain activity.Now, let's consider one more thing about gmy mindh. We believe that "my mind" performs a variety of activities: I see, I hear, I feel, I think, I remember, I speak, I judge, I decide, etc. However, it seems that this is not the case. Let's take, for example, the act of "I look at." The details were explained in the paper "What is ebeing visible?f", so I will limit myself to a brief explanation here.

.jpg)

@For example, let's consider a situation when "I'm looking at a coffee cup." Figure 2(a) shows a picture which is a little difficult composition to understand, but it represents the material world that spreads from behind some person to the front of that one. Certainly, in the "material world", the "act of looking at" can be defined. In other words, directing the eyes of the physical body to the coffee cup as a substance is the "act of looking at " itself. On the other hand, the "act of looking at" cannot be defined in the "world before our eyes" as shown in Figure 2(b). This is because the world before our eyes is the apparent material world and the body seen before our eyes is an apparent body, and it does not have eyes that are equipped in the physical body. Therefore, the apparent body does not have the function of "looking at".

.jpg)

@It can be said that the coffee cup before our eyes is an "apparent existence" that exists in that position because of the act of looking at. This is because the person in Figure 2(b) has the feeling that "I am looking at" but is not actually "looking at". To mask this fact, the gthought of I am looking at" is prepared to the opposite direction of the "apparent gaze" that we believe is equipped in the apparent body.

@Incidentally, since there is no color in the material world, the cups in Figure 2 (a), which represents the material world, and Figure 2 (c), which will be used next, are not colored, but the one in Figure 2 (b), which represents the world of the mind, is colored.

Additional Explanation

@I think it's unbelievable for you that the world before your eyes is the apparent material world created by brain activity. If this idea is wrong, then all my arguments that I am going to talk about will collapse to the core. Therefore, I would like to explain it from a different perspective.

.jpg)

@Look at Figure 2(c), which shows the scene of the material world in Fig. 2(a) from the side. A coffee cup is placed on the table. On the other hand, on the right, there is the physical body of a person who is looking at the scene. There is a complete physical separation between the two. The only thing that connects between the cup and the person's physical body is the electromagnetic waves sent from the cup, if we take visual perception as an example. There is nothing else that unites the two. Moreover, it is a one-way flow from the cup to the person, and there is no work from the person to the cup except turning the eyes of the person's physical body to the cup. However, just because the person looks at it, it does not mean that the material world itself is taken in. What is taken in is only electromagnetic waves, and all that is obtained from them is just the image of an upside-down and left-right inverted coffee cup reflected on the retina.

@However, when we turn our physical eyes to the coffee cup, the apparent material world, including the cup, appears in the world before our eyes as shown in Fig. 2(b), and we make the mistake of superimposing this situation on the material world shown in Fig. 2(a). As a result, we come to mistakenly perceive the world before our eyes as the material world.

@Certainly, it is an indisputable fact that the material world exists around our physical body, and I am proceeding with the discussion based on that premise. As our gaze shifts, the apparent material world continuously appears before our eyes, so it is natural for us to think that it is the material world and that we are looking at it.

@The confusion in this regard can be known from the use of two verbs in relation to the act of looking: "look at" and "see." If you are asked, "What are you looking at?", you will answer, "The coffee cup before my eyes." On the other hand, if you are asked, "What do you see?", you will answer "the coffee cup before my ees". You can know that the coffee cup before your eyes is interpreted in two meanings. To mask our misconceptions, there are two types of verbs: transitive verbs and intransitive verbs. Again, it is true that there is the material world around our physical body. The root cause of this misconception is the misinterpretation that the apparent body before our eyes is the physical body. As I mentioned earlier, it is explained in detail at Chapter 3, Section 4 of the paper "Where is the Mind?" and in Section 3-2 of the paper "What am I?", so I would appreciate it if you could refer to it.

Am I looking at something?

@The original meaning of the coffee cup seen before our eyes is that it is not a cup as a substance, but an "apparent cup" created by brain activity because of the act of looking at and it exists at that position. In other words, it is not "I am looking at the cup", but "The cup exists at that position before our eyes." Applied to Figure 2(b), the coffee cup seen before our eyes is not directly related to the act of "I am looking at", but it exists at that position where it is being visible. Therefore, the act that accompanies the gthought of eI am looking atfh in this case is an "apparent act", and "my mind" that accompanies the gthought of eI am looking atfh is not actually performing the gact of looking ath, so it can be said that it is an "apparent mindh. In fact, as I have already mentioned, the true meaning of the gworld of the mindh is the entire world before our eyes, including our own body before our eyes. From now on, we will distinguish the gmind as common knowledge" from the true meaning of the gworld of the mindh and name it as an gapparent mind".

@The expression "Objects exist at the position where they are visible" may seem the same as common knowledge. It is true in the material world. However, please note that what we are discussing is not the material world, but the apparent material world created by brain activity, that is, the world of the mind. It is not something a matter of course.

@The fact that we can know the existence of the coffee cup before our eyes even though we are not looking at it means that the object before our eyes is "existence and at the same time recognition". We tend to think that recognition is a high-level function that is different from the world before our eyes, and it takes place deep in the mind, so to speak, but even if it is a form of lower-order recognition, there is no doubt that "existing before our eyes" is a form of grecognitionh.

@In fact, the world we see before our eyes is the gworld of the mindh created by brain activity, so it is not particularly strange when we think like it. In addition, the fact that the existence before our eyes is also a recognition is important when coming to think about the gexistence of the eIf". Recognition is discussed in Chapter 4, Section 2 of the afore mentioned paper "Where is the Mind?", and in Section 4-2 of "What am I?" It is explained in detail, so I hope you will refer to it.

@We will also consider gexistence and recognitionh, later in section (2-2).

Am I thinking about something?

.jpg)

@Although the three papers mentioned above do not address this theme, let us consider the act of gI am thinkingh by taking Figure 3 as an example.

@First, mentally flip the shape shown in Figure 3(a) upside down, and then also flip that shape horizontally. I don't think this is a particularly difficult task. The result of what kind of shape this will become is shown in paragraph two steps below.B

@In the face of such challenges, I think we manipulate the shape before our eyes variously in our gapparent mindh by using the shape as a clue. Perhaps behind this, brain information processing works, and I assume that very short-term memory is involved in holding the image. At the same time, I think that through manipulating the image before our eyes, we hold the thought of gI am thinking.h It is undoubtedly true that the brain engages in the manipulation of images before our eyes as its function. However, as I mentioned earlier, there is no actual act of gI am looking at the shape before my eyes.h It's just gbeing visible.h Nevertheless, being to derive an answer suggests that while we have the thought of gI am thinking,h it must be said that this is merely an gapparent acth.

@The gexistence of the eI'h that accompanies the thought of gI am looking ath, as mentioned earlier, can be said to be an gapparent existenceh. In the same way, that the gexistence of the eI'h that accompanies the thought of gI am thinking ath can also be considered as an gapparent existenceh. However, even if we call it an gapparent acth or an gapparent existenceh, it is hard to believe that something utterly useless exists in the world before our eyes. The same can be said for the figure shown in Figure 3(a). It should serve as a clue for thinking. This point will be discussed later in section (3-1).

.jpg)

@The figure flipped upside down and left to right is figure 3(b).

@As another example, let's consider the case of solving a math problem. When we are taking a math exam, we think we can solve it but cannot solve it. The time goes by heartlessly, and we leave the classroom with a feeling of regret. After that. I suppose there are many people who have had the experience of suddenly knowing the answer, even though they have not thought about the problem.

@In another case, many researchers have said that new discoveries and ideas suddenly come to mind when they are relaxing, such as during taking a walk or taking a bath. Of course, before that, it is a prerequisite that they have taken enough time to work on the problem.

@As can be seen from these examples, we tend to think that problem-solving only occurs when we are consciously addressing it, because there is the thought of gI am thinking.h However, this is not the case. While it may not apply to all thinking, it is also true that the act of gI am thinkingh often results from the information processing of the brain automatically.

(1-3) Definition of the "I" inherent in the world of the mind

@I think it would be problematic to conclude everything from only two examples: "I am looking at" and "I am thinkingh, but it turns out that when we think "I am doing these acts" the "I" is not doing any specific acts, but they are "apparent acts" with no substance. In other words, if we interpret the acts that are carried out based on the thoughts of "I am looking at" and "I am thinking" as being carried out in "my mind," then it seems reasonable to think that "my mind" is gan "apparent existence" that does not involve substances.

@Therefore, the equation @ is will be expressed as following.

@the "I" (an apparent existence) = Apparent body + Apparent mind B

@What is indicated by the equation B will be redefined as the "I". In other words, the existence of the "I" consists of an "apparent body" and an "apparent mind", so to speak, and does not perform "acts involving reality". If we consider equation B from the opposite point of view, we can interpret it as the "I" being created from an "apparent body" and an "apparent mind" as shown in the following equation. It will be discussed in section (3-2).

@Apparent body + Apparent mind ¨ the "I" (an apparent existence) C

@Now, I would like to review how the mind is perceived by common knowledge. As the words, "knowledge", "emotion", and "will" indicate, "knowledge" represents looking, listening, thinking, speaking, remembering, etc., "emotion" represents joy, anger, sadness, etc., and "will" represents making decisions, doing, etc. Since all of these are thought to be carried out by brain activity, it can be said that the mind is created by brain activity. At the same time, it is necessary to pay attention to the fact that these acts are carried out under the "thought of the eIf ".

The thought of the gIhiÆ¢¤v¢ watasi toiu omoij

@It is generally believed that the "I" is engaged in acts related to knowledge, emotion, and will, based on the thought that "I am performing these acts." But it is not true. As I have just said, the gIh is not engaged in "acts of reality". However, as the thought that "I am performing these acts" exists, the existence of the gthought of the fIf" is not denied. As I mentioned earlier, when you think you are looking at an object before your eyes, it is true that there is a thought that "I am looking at it" in the opposite direction of the apparent sight line. However, it is undoubtedly different from what we think. This is because the "I", which consists of the "apparent body" and the "apparent mind," does not perform the specific acts that we think as common knowledge.

@The gapparent mindh that is accompanied by the gthought of the eIfh is different from the gapparent bodyh and cannot be directly recognized. If it is an gapparent bodyh, the existence in the world before our eyes is simultaneously recognition, so we could acknowledge its presence by directing an apparent gaze towards it. However, the other gapparent mindh cannot be directly recognized. We can only recognize its existence through the thought of "I am doing these acts." In other words, we can only recognize its existence through thoughts like "I am looking at", "I am thinking", and so on. This must be the reason why the gexistence of the eIfh which consists of an apparent body and an apparent mind is an elusive and mysterious existence.

@The phrase of the "thought of the fIfh may be like the philosophical term of gSelf-Recognitionh or gSelf-Consciousnessh. Indeed, there may be similarities, but since the gthought of the eIf" is a concept tied to "acts", as seen in expressions like "I am looking at." etc., I will use it as a term with a meaning different from the philosophical terms. However, it is a fact that the gthought of the eI' and gself-recognitionh are similar, so for the time being, it is acceptable to interpret both as having the same meaning and proceed with the reading.

@One point I would like to point out here is that when we say, "my mind" consists of knowledge, emotion, and will, then the "thought of the eIf" serves as the core of the "apparent mind". It will be discussed the details later in sections (3) and (4) of (3-2).

Sorting out the words

@In addition to the fact that the story is difficult to understand to begin with, I think that the use of confusing words makes the story even more difficult to understand. Therefore, I would like to clarify the meaning of the words and summarize the story so far by using figure 2 again.

@First, the meaning of the word "apparent" is different from what we think in common knowledge. It is used in two main meanings.

@The one is when we focus on "existence". Namely, the goriginal objects exist in the material worldh. These are the terms; the gapparent material world", "apparent objects" and "apparent physical bodies", and they correspond to the "material world", "material objects" and "physical bodies". In summary, it looks like this:

@the apparent material world¨ the material world

@apparent objects¨ objects as substance that exist in the material world

@Another one is when we focus on "acts" as opposed to "existence". For example, the act of "I am looking at" that I mentioned earlier is the case. It is true that the physical body performs the act of looking at, but in the world before our eyes, although we are directing our apparent gaze to apparent objects, we are not performing an act that involves any reality. Or, as another example, when we reach out for the coffee cup before our eyes, it is true that in the material world the physical hand is extended toward the cup, but the apparent hand before our eyes does not extend it toward the material cup.

@Since the brain is engaged in various activities, it is true that it is processing information such as vision. But under the definition that the world created by brain activity is the world of the mind, the term "apparent acts" is not used to mean that the "I" is engaging in those acts that are accompanied by those entities.

@The expression an gapparent mind" expresses that is located at the head of the apparent body and does not perform any substantial acts, while the true meaning of the gworld of the mindh is the whole world that spreads out before our eyes. Please note that it is different from the gmind as common knowledgeh.

@The term gapparent the eIfh is used in the same meaning as the gIh that is consisted of an "apparent body" and an "apparent mind".

@This paper deals with the gI" as an "apparent existence". It can be summarized in the following figures.

Explanation by using figures

@Now, let's summarize what we've talked about so far using Figure 2 again. Fig. 2(a) represents the material world. In the world a physical body exists, and information is processed by the brain located in the head. This represents the state indicated by equation A.

@On the other hand, Figure 2(b) shows the gworld of the mindh as a whole, representing the world of the mind created by brain activity. It's a confusing figure, but it's the world that is seen through my eyes or your eyes. In the "world of the mind", a coffee cup is depicted, which is an "apparent object", as well as the arms and legs, which are part of the "apparent body" of mine or yours.

@The "apparent mind" cannot be directly represented in the figure, but is in the head of the apparent body and is indirectly recognized by the apparent acts such as "I am looking at", "I am thinking", etc. To put it another way, it shows a situation in which the gIh, consisted of the apparent body and the apparent mind, is inherent in the world of one's own mind. This illustrates the situation shown by equation B.

@It cannot be directly represented in the figure too, the "apparent gaze" is directed at the "apparent coffee cup". As I mentioned before, the apparent body is not equipped with eyes. There is also no brain to process information. Nonetheless, the thought of "I am looking at" is created in the reverse direction of the "apparent gaze". Or the thought of "I am thinking" is also an apparent act. Therefore, it is an "apparent mind" or an "apparent the eIf" who is supposed to be doing such activities.

@In the paper "Where is the mind?", the terms the "apparent mind" or the "so-called mind" are used, while in the paper "What am I?", the term "apparent mind" is used.

@This paper will proceed by using the term gapparent mindh.

Summary of the paper "Where is the mind?"

@This is the overview and supplementary explanation of the paper 'Where is the mind?' In summary,

@@The world and the body that we see before our eyes are the apparent material world and the apparent body created by brain activity. The world created by brain activity is defined as the gworld of the mind", then they are all apparent existence inherent in the world of the mind.

@A In the world before our eyes, acts such as gI am looking ath do not exist, they are gapparent actsh. The fact that we can recognize the existence of objects before our eyes means that they are existence and simultaneously recognition.

@B The "I" consists of the "apparent body" and the "apparent mind" and is "inherent in the world of one's own mind". On the other hand, the "thought of the eIf" exists in the opposite direction of the apparent gaze, based on the gthought of being performing these acts". It cannot be directly recognized, can only be recognized by the gthought of being performing these acts".

@CThe word "apparent" does not mean meaningless or unnecessary, but it has different meaning from common knowledge. In fact, the brain will not create unnecessary things, and as will be discussed in (3) of (3-2) later, it can be thought that the gapparent objectsh play important roles in information processing.

August 2025@Shigeru Shiraishi

Return to the top of this paper

Copyright(c) 2025 Shigeru Shiraishi All rights Reserved